News

Rahul Dravid: A shining light that continues to serve Indian cricket

FEATURE

FEATUREOn this day in 1973, one of the all-time greats was born in Indore

If there was ever an example of ‘giving back to the game,’ Rahul Dravid’s name is easily amongst the first ones to come to mind. Yes, many have different ways of giving back – be it as a selector, as coach or as president of the BCCI, but Dravid has shaped the future of Indian cricket, by taking some talented individuals under his tutelage and turned them into international material.

The results are there for the world to see. In 2016, he took over as the mentor of Delhi Daredevils (now Capitals) and groomed youngsters like Shreyas Iyer, Prithvi Shaw, Rishabh Pant and others. Then later on, he went on to guide the Indian Under-19 team, which won the World Cup in 2018, where India discovered another gem in Shubman Gill – all of whom have been tipped to be India’s future.

Not just Under-19, but Dravid was also the coach of the India A team and most recently, it was Hanuma Vihari who credited the Indian great for the role he has played in his career, ahead of his Test debut against England.

The transition

As a player, he was par excellence and his grit, determination and hard work, which led him to playing 509 times for India. Earmarked as a terrific talent, while Dravid’ temperament was not much of an issue in the Test arena, he had to adapt to the 50-over format which was not easy as his first three years was nothing to boast about having scored 1,709 runs at 31.65, which included a century and 12 fifties. However, he was backed by the management and his captains Sachin Tendulkar and Mohammad Azharuddin as they felt it was just a matter of time he could translate his form into ODIs.

It turned out to be the right call as in 1999, he scored 1,761 runs at 46.34, which included six centuries and eight fifties. He was also the leading run-getter in the 1999 World Cup, where he also became only the second player to score back-to-back centuries in the mega event. The year also saw Dravid build two 300-plus partnerships – one against Sri Lanka at Taunton and the other against New Zealand in Hyderabad – in which he scored 145 and 153 respectively. He never had a more prolific calendar year after that in ODIs.

Not just his appetite for runs, but the pace at which he got them too was incredible. Between 1996 and 1998, Dravid had a moderate strike-rate of 63.46, but in the year 1999 alone, it was 75.16.

Aye, aye captain

“Ask him to walk on water and he'll ask, ‘How many kilometres?,’ Harsha Bhogle once said of Rahul Dravid. Considering that he kept wickets, captained, opened and batted literally everywhere he was asked to and excelled, Bhogle’s words were not completely far-fetched.

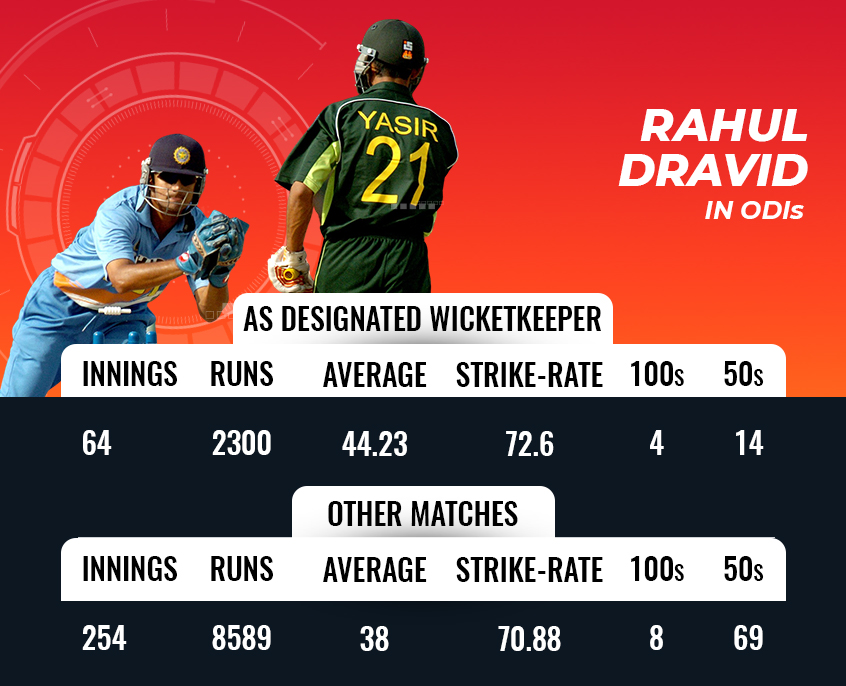

In what was initially set to be a temporary move, it turned out to be a career-altering decision not just for Dravid, but it turned out to be a sound, sensible move for Indian cricket too – making Dravid India’s regular wicketkeeper. He kept wickets for the first time for India when Nayan Mongia was injured in a World Cup game against Kenya. He would play his first game as a designated wicketkeeper for the first time against Sri Lanka in the very next game.

Dravid is no stranger to ‘keeping wickets, but was one when it came to the international stage. By his own admission, he was never naturally gifted. In fact, he put his hand up during an inter-school selection as he felt it was the best way to be selected. That would eventually go on to serve Indian cricket for over five years.

With Dravid taking over the gloves, it gave India an opportunity to play an extra batsman or a bowler. More often than not, it was Mohammad Kaif who benefitted from Dravid’s selfless act, including playing in the 2003 World Cup, where India made it to the final for the first time since 1983.

As far as Dravid the batsman is concerned, donning the gloves had no impact on it whatsoever. In fact, both India and Dravid benefitted from that move.

A genius outside the subcontinent

While scoring 10,000-plus runs in ODIs is no joke, it is his achievements in the Test arena for which he will be a little more renowned for. His match-winning/saving centuries, his monumental double tons or even be it for his catching in the slip cordon, Dravid gave everything on the field. He was not particularly a gifted athlete, but his temperament, mindset and also his skills made him better than most. He was never drawn into mind games or sledging that was ever-present in the Australian teams of the Steve Waugh or the Ricky Ponting era.

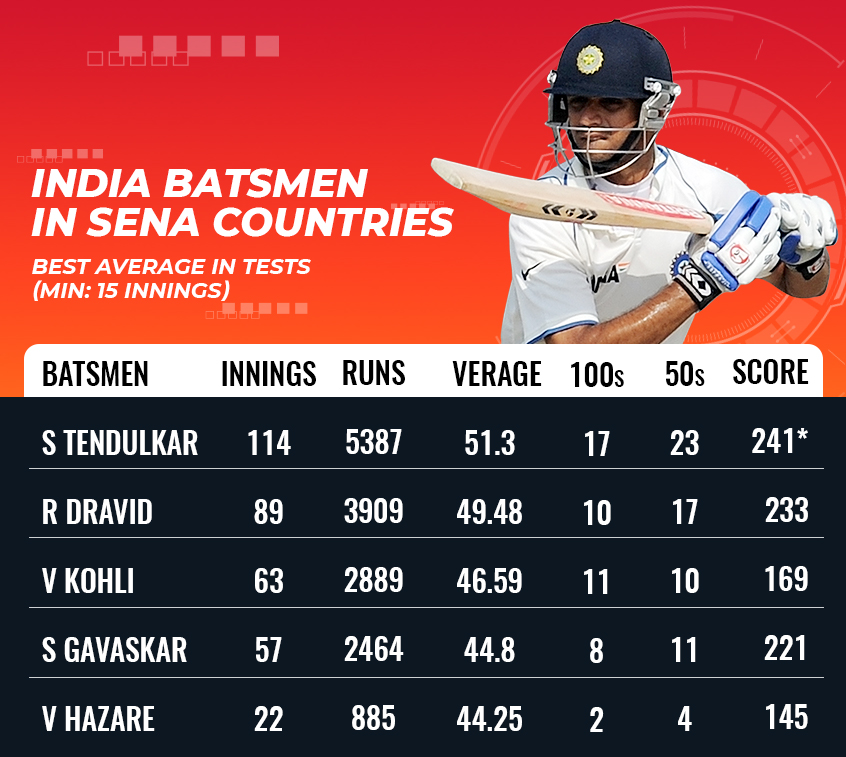

For the Indian batsmen, for that matter, all batsmen in the world are judged how well the play away from home. For Australians, for instance, they are either good or bad based on the runs they have accumulated in the dustbowls of the subcontinent. Similarly, for Indians, while you may have scored bucket-load of runs at home, what makes you a great batsman is the amount of runs you have scored outside the subcontinent, specifically in South Africa, England, New Zealand and Australia – commonly known as the SENA countries. For India, these countries are the toughest to visit even for someone of the calibre of Dravid, but he took on the challenge.

He averaged 48.54 in these countries, which included a couple of handy knocks – his 148 in Johannesburg which almost gave India their first win in South Africa in 1997 a or his twin centuries in Hamilton in 1999 that took India to the cusp of a rare win in New Zealand.

However, one of his finest efforts came in England in his final Test in England in 2011 when he scored an unbeaten 146 opening the batting and carried his bat through. He had batted for 378 minutes and played 266 balls. Yet, after a short innings break, he strode out to bat again, but this time lasted just 32 balls in a 49-run opening stand with Virender Sehwag. Of course, nothing could perhaps beat the 180 against a strong Australian side at the Eden Gardens in 2001 – a match India won after following-on or the double century, again, against Australia in Adelaide two years later.

By the end of his Test career, Dravid’s defence, which was his strength all those years, slowly started to become his weakness. His was getting bowled more often than ever, which raised questions if he had indeed lost his edge in the longest format. With the likes of Cheteshwar Pujara, Ajinkya Rahane and Virat Kohli slowly knocking on the doors, Dravid walked out of international cricket without a fuss, leaving behind a legacy, which is hard to replicate and yet, he still continues to have an impact on Indian cricket.