ANALYSIS

ANALYSISWhen Dean Elgar named the playing XI after losing the toss in Centurion, the absence of Duanne Olivier certainly sprung a surprise. In the next two hours, there was mass confusion, South Africa lost the plot with the ball and yet, the reason was rather unknown.

Olivier returning in South African whites is more anticipated than anything in South Africa’s recent Test history. When he flew to England for a Kolpak deal, the curtains were drawn on his Test career. He was a real villain. Kolpak, South Africa, Test careers, everything together reads the recipe for disaster.

But when he left at the age of 26, there was no hopes that he would return. And at the age of 29, he has not just returned, he has been viewed as the point of difference in the South African bowling attack. At the Wanderers, he was exactly that, the difference.

Never has a bowler in the recent past had a threatening effect bowling in the 120 kmphs, heading towards the 130 mark. Never has a bowler struck at such a threatening rate, barring Vernon Philander. So, it was only right that Olivier’s return was marked with a loud cheer, a roar inside the South African dressing room.

He wasn’t fast but he ensured that every one of his delivery hit the splice of the bat. Accurate, threatening and mean, Olivier’s return in the Proteas setup was a spring in the steps of the bowling attack. Suddenly, they looked far more threatening, as a group rather than individuals walking away with the accolades.

"We are here to compete. We are not just going to roll over. For me, that's very important: throwing the first punch, to know that you are here, you are present," said Olivier ahead of his return to ESPNCricinfo.

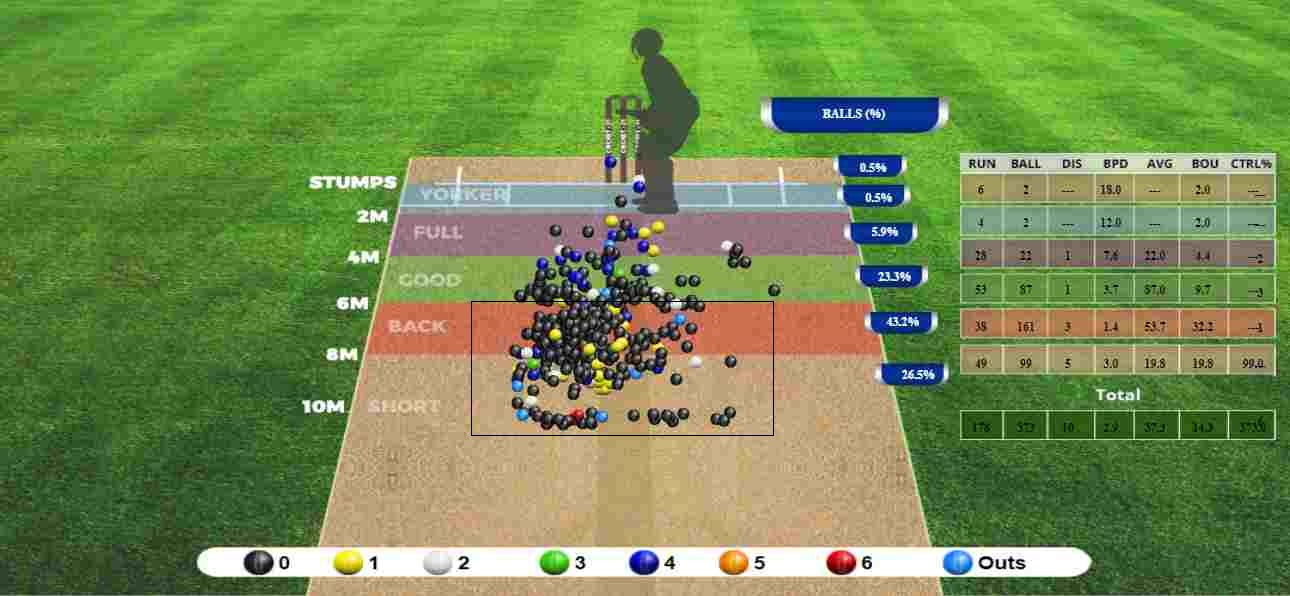

Even in the likes of Lungi Ngidi and Kagiso Rabada, Olivier stood as a glue, stood as that X-factor that they missed, pulling the length back while upping the fire. Only 24.4% of his deliveries during the first half of the day were pitched up, only 7.7% pitched right up in front of the batter’s eye.

Barring that, he picked a line that was a tough prospect for the Indian batters. Even at his pace, he looked threatening every time he delivered the ball. And the others rightfully joined, targeting the blind zone that hurts India. There was a pattern in play, the shorter South Africa were, the better the results.

Hard hitting questions, shorter lengths

After the historic win, the Indian batting was on an all-time high, they showed signs of transforming into a beast of a side in overseas conditions. But like their trip to Wanderers last time around, India learnt the lessons in the worst possible fashion. Following an easy start, where KL Rahul and Mayank Agarwal took off, South Africa struck back.

Wait, they didn’t just strike back, they struck a lusty blow. Mayank was caught in the perfect of two minds and he chose to attack, showing that this India isn’t afraid to attack. But at the same time, his shot-selection was rather unwarranted, chasing deliveries that weren’t a trouble to his wickets.

Time and again, in position of ascendancy, India’s lack of control over the knob between aggression and defense has rather cost them dearly. In all fairness, India’s bowling attack could dismiss South Africa for under 150 but the major point here, is how India fell dearly to their old enemy – the fear against the shorter ball.

Against Cheteshwar Pujara, Olivier, who returned, was effective, not just for his testing lines but rather for his length, that found a little bit of zip and extra bounce. Pujara’s dismissal was yet another painful event in a Test. It is almost like he finds himself in the most awkward of positions.

There is no doubt over Pujara’s wealth of experience and quality but his dismissals, rather the sameness of it is worrying. Ajinkya Rahane, who in Kohli’s absence walked at No.4, saw a similar fate to his own tale, getting out the very first delivery.

It showed what bowling at the Wanderers is all about, sticking to the line and lengths that are tougher for the batters. Rabada, who has had a tough series copied the tactics employed by the other two pacers, held his length back and the spongy nature of the pitch did the rest of the work to send back Hanuma Vihari. From the other end, Jansen wasn't a roll-over, he accounted for Agarwal, then sent in-form Rahul packing before he picked up both Pant and Ashwin, which in essential accounted for all the top batters in the innings.

Rahul and Ashwin show the way

While South Africa asked the tough and boiling questions, the Indian batting made scoring look tough, tough and tougher. But amidst the struggle was KL Rahul, Rishabh Pant and Ravichandran Ashwin, who showed technique, composure and more importantly, runs against their names. What Rahul exhibited was a batting masterclass in South Africa.

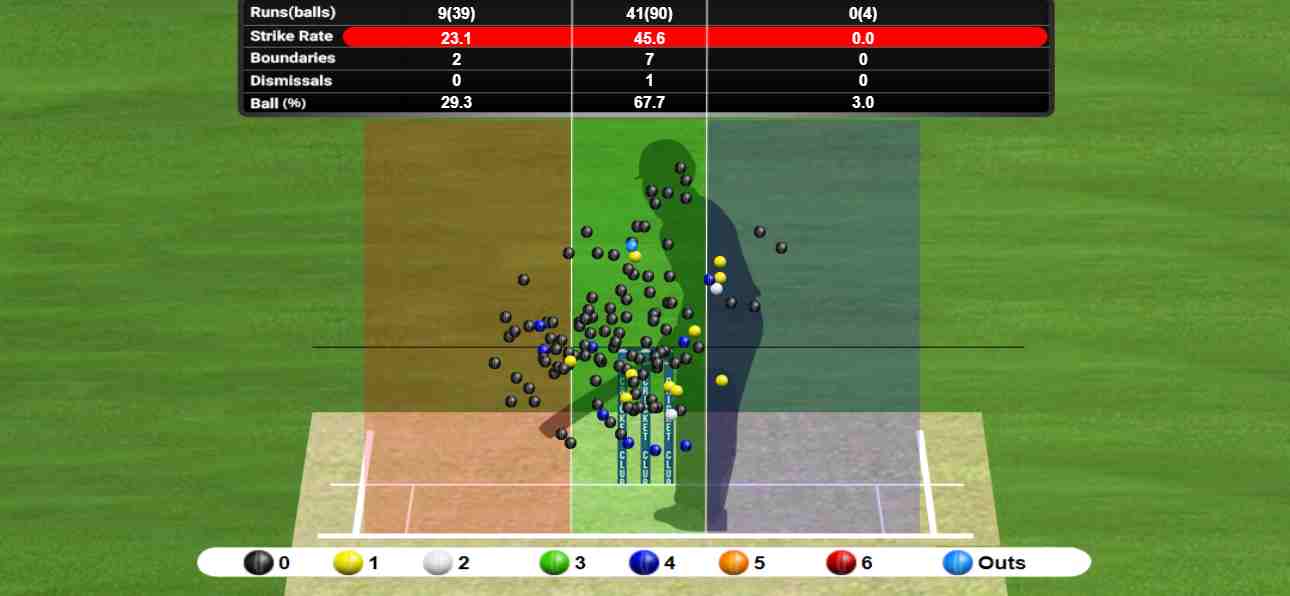

Like his innings in Centurion, the Indian stand-in skipper showed excellent control, not just over where his off-stump was but also over controlling loose drives. Out of the 39 deliveries outside off, Rahul scored nine runs, out of which two were boundaries. But once the ball was onto the stumps, which is 67% of the deliveries he faced, Rahul struck at 45.6.

His downfall was rather a tough one to swallow, especially after how he dodged rash shots in the first session. The partnership between Rishabh Pant and Ravichandran Ashwin definitely was a stern lesson to the other batters. While Pant was undone by Jansen’s angle, Ashwin showed how there was runs on offer, provided the technique was in play.

Against Ashwin, teams have often employed the short ball strategy and South Africa mixed it up, bowling both short and mixing it with fuller deliveries. The Indian all-rounder was a perfect concoction of calm and aggression. He wasn’t afraid to take the risks and he wasn’t reluctant to bat it down.

Anything that was fuller and pitched up, from 2-6m, Ashwin scored 30 runs off just 18 deliveries. And off the shorter deliveries, in the 32 deliveries, he only got 16 runs, showing tall technique against the challenging bowling attack. Time and again in his innings, the off-spinner was sterner in hitting the ball straight, avoiding the risk of playing a loose drive.