OPINION

OPINIONIn the one-off Test between Zimbabwe and Bangladesh in Harare two weeks ago, the visitors were reeling at 132 for six when Mahmudullah walked out to bat at number eight. He is too good a batsman to walk in at eight but such was the depth in that Bangladesh line-up. Shakib Al Hasan’s presence allowed him to bat at eight despite delivering only four overs of his off-breaks in the two innings combined.

Mahmudullah, alongside Liton Das, resurrected Bangladesh’s innings with a 138-run stand. That was not it though. He combined with the number 10, Taskin Ahmed, to add another 191 runs for the ninth wicket. Taskin scored 75 off 134 balls himself. The deep end of Bangladesh’s batting transformed a crisis into a daunting total that helped them dictate the Test to a 220-run victory.

Lower-order batting – number eight onwards - has become more salient than it ever was. It could be one of the consequences of white-ball cricket where the teams like to bat deep. The comprehensive demand has now spread its wings to Test cricket by producing more bowlers with some sort of batting expertise. Gone are the days when the two captains would come at a mutual agreement of not bowling bouncers at the tail-enders before the start of a series. Now, the significance of their runs have shifted from a mere formality to a potential deciding factor.

A major factor that has brought the lower-order into the limelight is the universal fall in batting averages in Test cricket. Since 2018, the top seven batting positions have averaged 33.5. It is a dip of 4.3 runs per wicket from the previous four-year cycle - 2014 to 2017. None of the four years since 2018 has seen a batting average higher than any of the calendar years between 2001 to 2017. It is clear that Test averages have come down whatever the reasons maybe. The bigger the dip, the greater will be the impact of the runs scored by the lower-order.

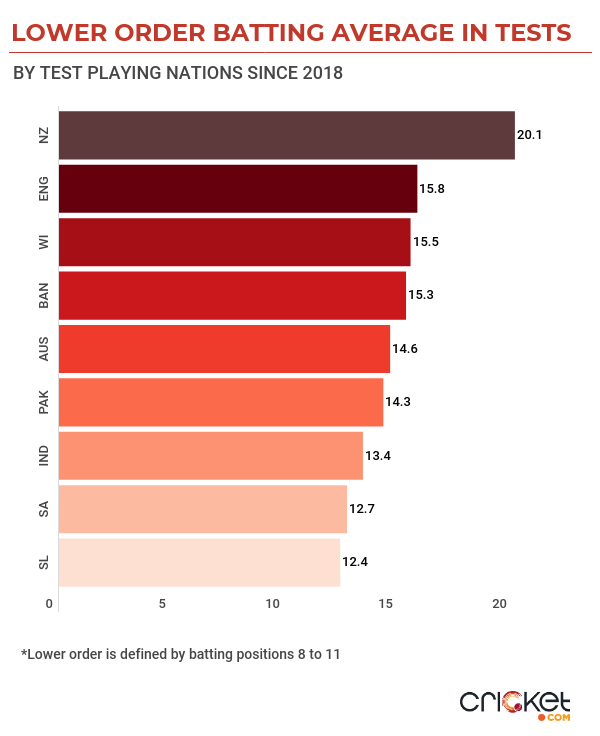

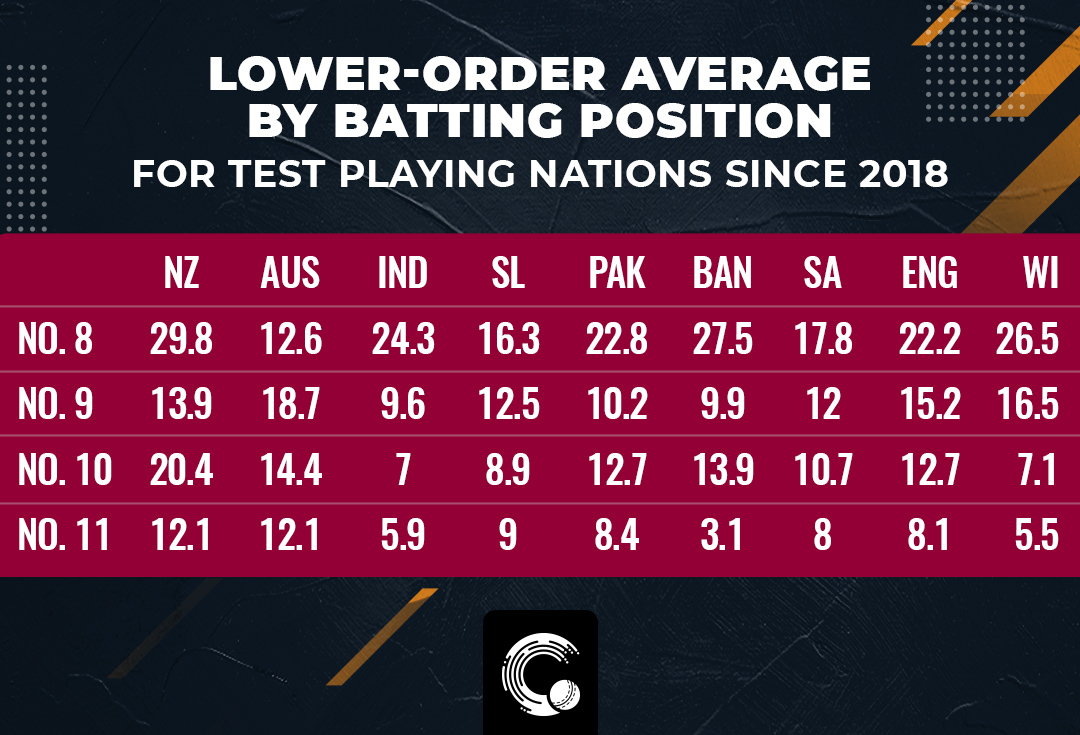

A high proportion of the average in the above graphic is governed by the number eight. The teams in the top half have a strong number eight. New Zealand have Kyle Jamieson, Mitchell Santner and Tim Southee. England, no matter what combination they play, always have players with a few first-class hundreds batting till nine or ten. West Indies have Jason Holder who averages 31.8 with the bat in Test cricket.

A high proportion of the average in the above graphic is governed by the number eight. The teams in the top half have a strong number eight. New Zealand have Kyle Jamieson, Mitchell Santner and Tim Southee. England, no matter what combination they play, always have players with a few first-class hundreds batting till nine or ten. West Indies have Jason Holder who averages 31.8 with the bat in Test cricket.

Interestingly, India, in the bottom half here, also have a potent batsman in R Ashwin occupying that spot. Yet, they suffer with their lower-order, primarily because of minimal returns from numbers nine, 10 & 11.

However, the dynamics of Test cricket which brings conditions into effect more than any other sport put the emphasis on where these runs are scored instead of who scores them.

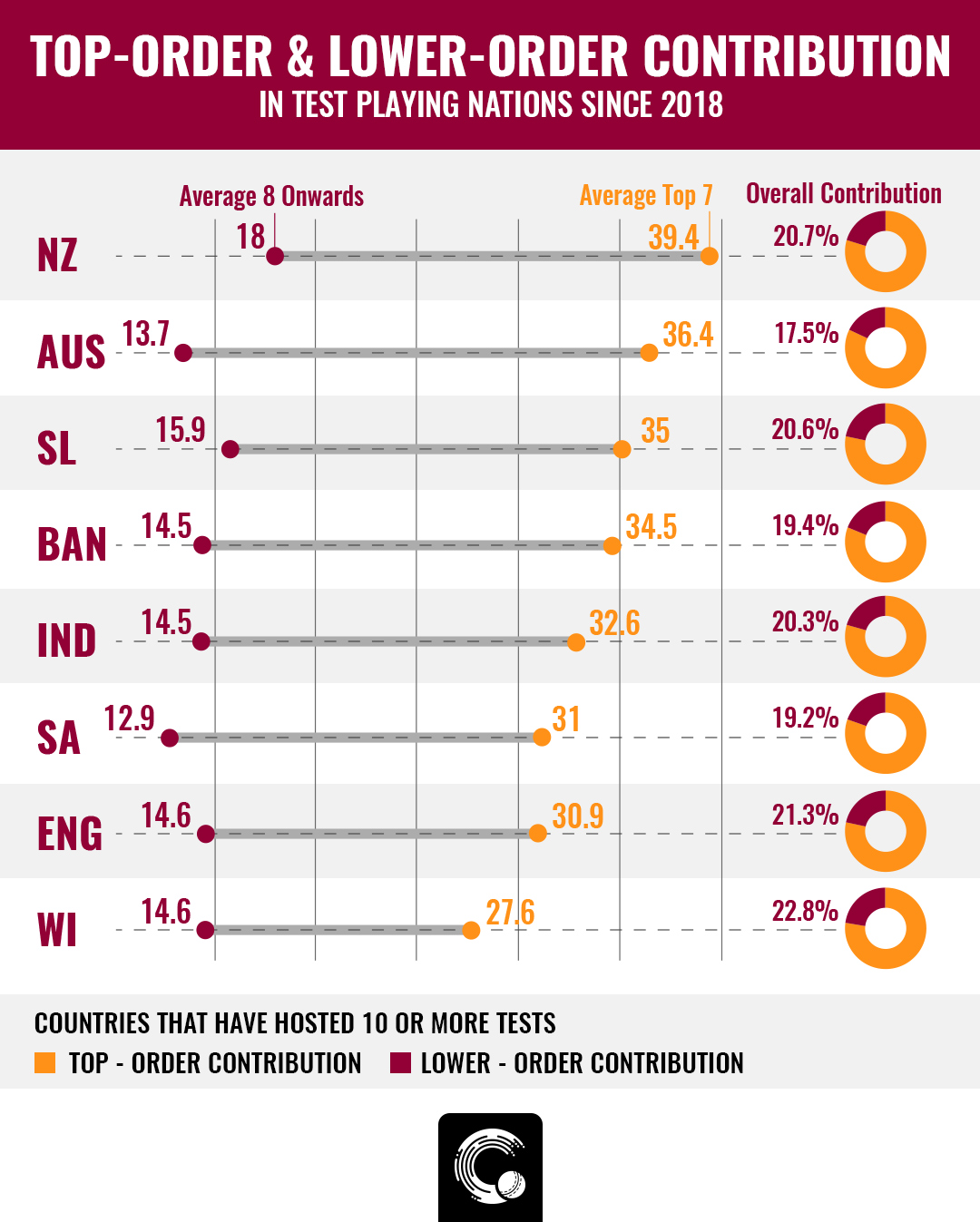

Currently, New Zealand and Australia are easier countries to bat in. Sri Lanka and Bangladesh follow. Runs from the lower-order are an added luxury here as the top-order is expected to perform.

But this piece underlines the necessity of the lower-order runs and hence the focus shifts to West Indies, England and South Africa - countries with the lower batting averages for the top seven.

The batting average for the lower-order in India, Bangladesh, England and West Indies are nearly similar. On that basis, the lower-order is expected to add 57-59 runs to the total. The number is the same but is of a lot more value in the latter two countries where the expected contribution by the top order is 216 and 193. The lower-order has thus added 22.8% to the total in West Indies and 21.3% in England, the most in any country since 2018. This underlines these two countries as the most significant for the contribution from the lower-order. South Africa is another country where the lower-order can be handy but have not cherished the prospects.

The batting average for the lower-order in India, Bangladesh, England and West Indies are nearly similar. On that basis, the lower-order is expected to add 57-59 runs to the total. The number is the same but is of a lot more value in the latter two countries where the expected contribution by the top order is 216 and 193. The lower-order has thus added 22.8% to the total in West Indies and 21.3% in England, the most in any country since 2018. This underlines these two countries as the most significant for the contribution from the lower-order. South Africa is another country where the lower-order can be handy but have not cherished the prospects.

Another aspect that deems the the lower-order batsmen dangerous is the degree of freedom associated with their batting on occasions. They do put a price on their wicket but they do not have their lives or career dependent on it. Hence, they can afford to be a little more adventurous in tough scenarios, a privilege that eludes the top-order batters.

The prime example is the World Test Championship final. Only 34 runs were scored at a run-rate of 1.5 on the penultimate morning as the contest was heading towards a draw. In the second session, New Zealand picked up the run- rate, scoring at 4.2. Kyle Jamieson struck 21 off 16 in a 30-run stand with Kane Williamson. Tim Southee scored 30 off 46. The session opened the possibilities of a result and the Kiwis got through.

In that innings, New Zealand’s last four batters scored 58 runs combined - 23.2% of the total of 249. The magnitude of their contribution and the speed at which they scored were both crucial to the outcome of the match.

What does it mean for the upcoming England-India series?

The WTC final marked the nth occasion of India suffering at the hands of the opposition’s lower-order. Time and again India have failed to dismiss the opposition lower-order but the difference becomes broader when their own lower-order fails to score.

Since 2018, India’s lower-order average 11.8 when on tour and concede at 18.6 to the opposition. Meanwhile, England’s lower-order have averaged 17.3 at home. There is a considerable difference which can be the deciding factor given the lower-order runs runs are of high importance in England.

Recalling Mahmudullah’s example at number eight, possessing all-rounders is an imperative part of creating batting depth. For India, the options lie in two spinners - Ashwin and Ravindra Jadeja. In England, they may have to choose one of those which lengthens their tail with four pacers. India is just not blessed with pace-bowling all-rounders like some other countries. In comparison, England have an army of seam-bowling all-rounders which once allowed them to play Jos Buttler at eight as a non-bowling asset.

Overall, India is stuck between the predicament of fielding their best bowling attack or playing Shardul Thakur in search of runs at the back end.

Lower-order batting, or tail end batting as it was called earlier, used to be the most ignored aspect of cricket. Commentators have been heard reiterating the joy of watching two tail-enders bat innumerable times purely on its imperfection. Cricket was already a batsmen’s game and now it requires the bowlers to bat as well. But probably such is the beauty or the intricacies of this sport that the imperfection has now become an important yardstick to maintain.